Wildfire Season Outlook 2025

A look ahead to see what could be in store for western Canada.

Kyle Brittain

4/26/20258 min read

As soon as the snow melts, it’s fire season.

At least, that’s the case throughout much of the boreal forests of western Canada during the spring. The winter snows have retreated in recent days, exposing the dead, organic material lying on the forest floor from last season. This material can quickly dry out, at the same time that moisture content in surrounding coniferous foliage is at its lowest during the year. Together, this fire-adapted landscape has conspired to make high-intensity fire more likely as soon as warm and windy weather returns. Then all that’s needed is a spark.

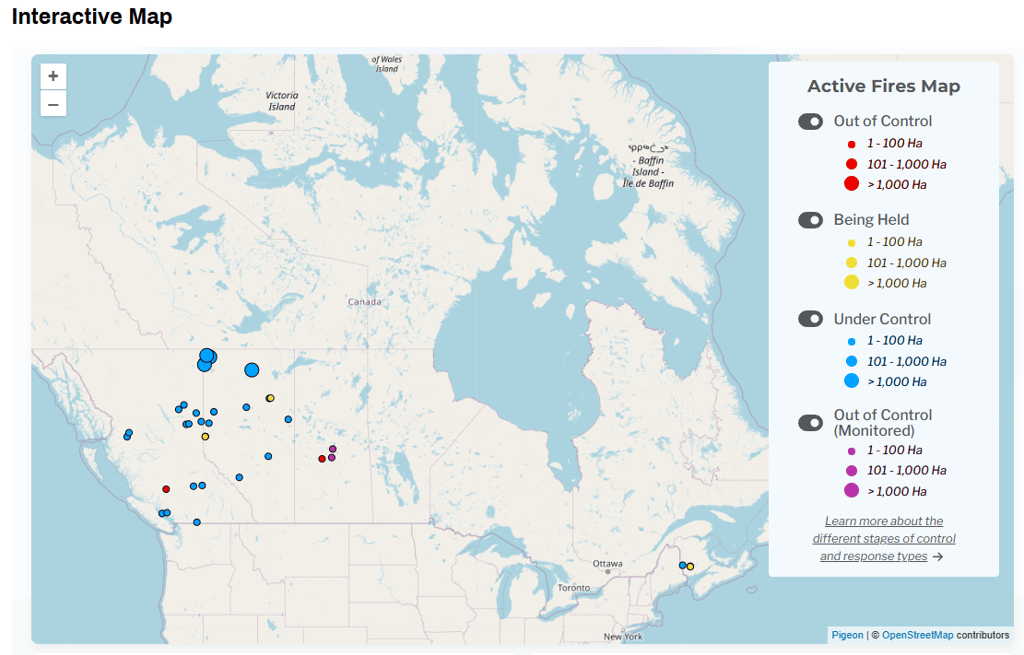

Active wildfires as of April 25th. Credit: CIFFC.

For these reasons, Alberta’s wildfire season tends to peak in May. This year could be no exception. At the time of writing on April 25th, the wildfire situation is pretty quiet out there, with a few of the first, small fires popping up. But that could quickly change, as the first warm days will likely arrive before the middle of May.

In contrast to the cold forests east of the Rockies, BC’s mountain forests tend to have a later start to fire season. This is often why we can have two separate periods where we’re choking on smoke in the Prairies – late spring, followed by late summer. Once again, for reasons we’ll soon see, this year could be no exception.

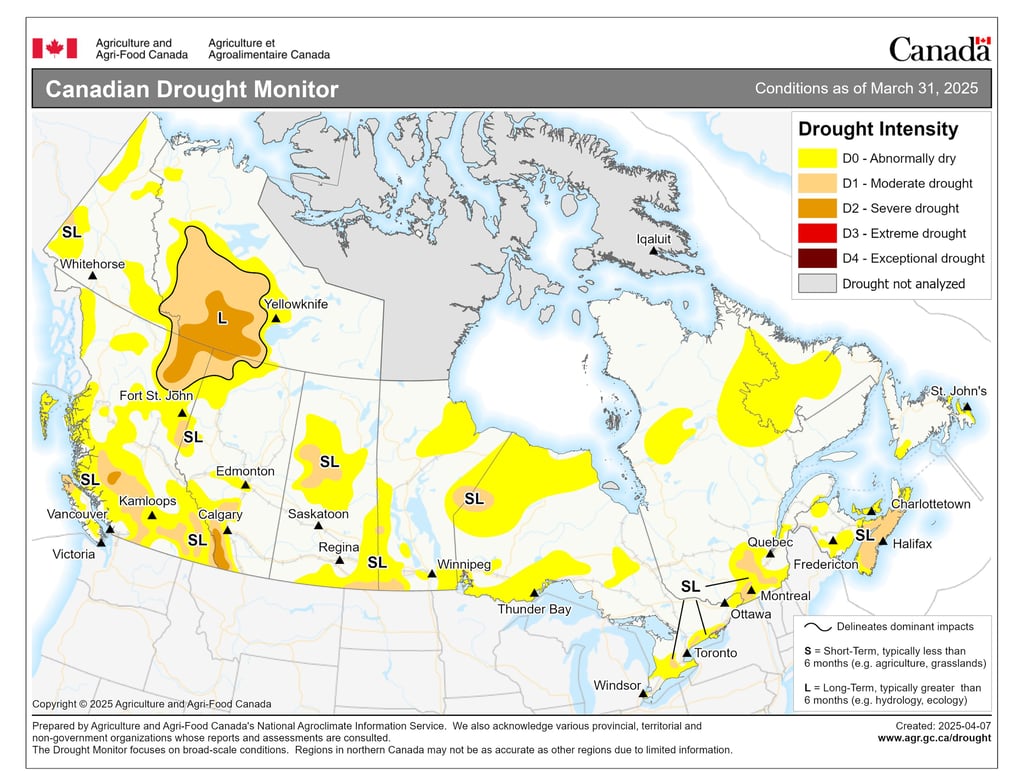

Pockets of severe drought exist in southwestern Alberta and British Columbia’s Cariboo/Chilcotin regions, where winter snowpacks were well-below normal. Further north, a persistent patch of drought continues to support wildfires that were ignited in 2023. Credit: Canadian Drought Monitor.

Drought is a significant factor in wildfire, but is not always required – especially in spring. On windy days, fires can quickly spread from the dry, flashy fuels on the forest floor into the upper canopy of the trees, regardless of how dry the soil is. So just because the drought monitor may show little or no drought in some areas of the boreal forest, doesn’t mean wildfire isn’t possible given the right weather conditions.

The notable blob of drought in northwest Alberta, northeast British Columbia, and southern Northwest Territories persists, supporting fires on the landscape that have now survived two winters. To the south, a low snowpack in parts of British Columbia’s Cariboo/Chilcotin region could support an earlier start to wildfire season there.

In southwestern Alberta, we’re praying for snow and rain. Not only could we run into summer water shortages in our river basins if current trends persist, but these dry conditions could also support elevated fire danger as we get into summer. As Mike Flannigan mentioned in our video on this year’s fire outlook, it’s only a matter of time before we see a significant incident in the Bow Valley, which includes Canmore and Banff.

Early spring was quite wet across parts of southern British Columbia, leading to a nice green-up in some of the interior valleys. Late May through June also tends to be the wettest time of year across much of British Columbia and Alberta, and the degree to which we receive this precipitation can influence how the rest of the season plays out. However, a wet start to the season, followed by a hot and dry back half can actually lead to more intense surface fires later in the season. This is because fine fuels, such as grasses, can grow quite thick during wet periods before drying out and becoming an abundant source of fuel.

Fire Season 2025

As discussed in my recent drought outlook, long range forecasting can be very challenging – especially in summer. This is because patterns that can drive weather on seasonal scales, such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), tend to be much weaker during the summer compared with the winter. This means that things like sea surface temperature patterns and drought play a less obvious and more complex role in shaping the atmospheric circulation. The weather we experience, along with the general “flavour” of the season tends to come down to what the jet stream does.

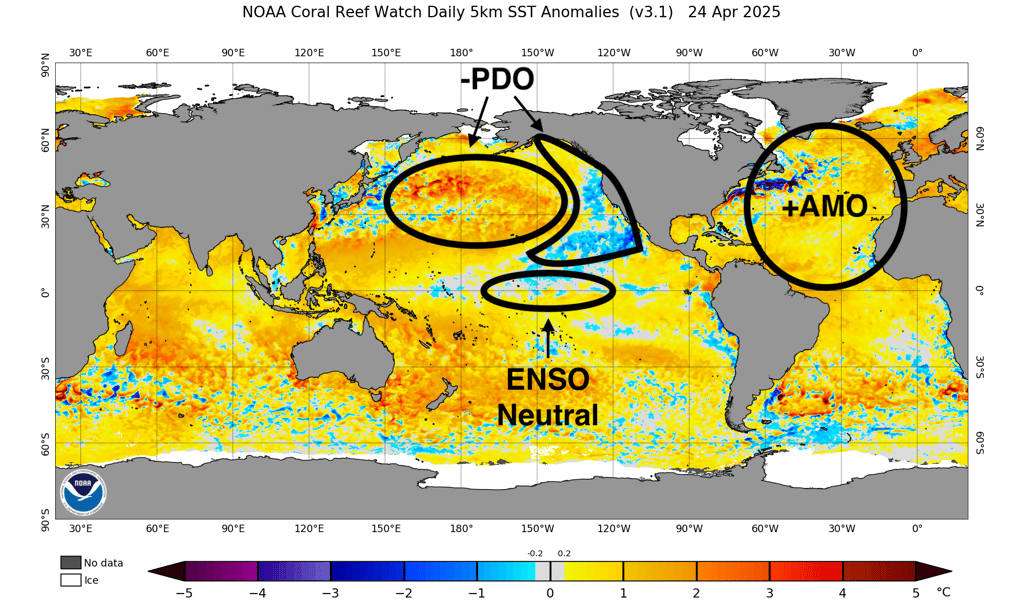

The analog forecasting technique can offer some skill, which involves looking at other years in the past that had similar characteristics throughout the land and oceans. This year, my top five analogs are 1967, 2009, 2018, 2001, and 2021 – based mainly on spatial patterns of sea surface temperatures and drought, which can go on to influence the shape of the summertime jet stream. Specifically, these years have similarities in several important ways:

The transition from (weak) La Niña conditions in the previous winter to ENSO neutral in the central and eastern tropical Pacific through the summer

Colder than average sea surface temperatures along the west coast of North America, representing the cold, or negative phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)

Spatial patterns of drought across North America

Warmer than average sea surface temperatures across the North Atlantic, representing the warm, or positive phase of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)

As of late April, ENSO neutral, negative PDO, and positive AMO conditions exist in the oceans around North America. Credit: NOAA.

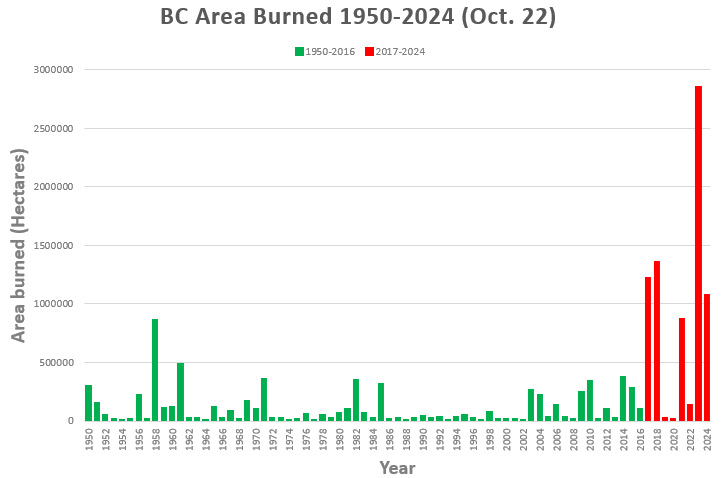

While it certainly doesn’t guarantee how this year will play out, most of these years were quite bad for wildfires in British Columbia, including 1967, 2009, 2018, and 2021. In fact, the top 5 worst fire seasons in terms of area burned in BC have occurred since 2017, with 2017, 2018, 2021, and 2023 all occurring in years transitioning out of weak to moderate La Niña.

This is likely due to the preponderance of a weaker and wavier jet stream that is more prone to getting stuck in “blocking” patterns in such years, especially with the ongoing cold PDO pattern. This results in frequent, strong upper ridges that cause sinking air on the large scale over western Canada, bringing long-lasting hot and dry weather while deflecting moist storm systems away from the region.

Research on trends in Canadian and Alaskan fires in the 20th century indicates that large fires are more common in British Columbia during La Niña/cold PDO years. East of the Rockies, the reverse tends to be true, with large fires being more common in El Niño/warm PDO years. While there are certainly exceptions (including 2001 in British Columbia – one of my analogs), it would seem the dice are loaded for an active fire season in British Columbia yet again in 2025.

The only glimmer of hope for fire and smoke-weary western Canadians is that such large-scale patterns tend to oscillate on the scale of years or decades. So, while a warming climate will almost certainly continue to lengthen and worsen the bad fire seasons in years to come, we could swing back into a wetter and quieter period in British Columbia again in the coming years.

There has been a notable increase in British Columbia’s area burned over the past 8 years. This has been following a gradual upward trend since the early 2000s, with some year-to-year variability. There was also a notable quiet period through much of the 1980s and 1990s, which most residents of western Canada alive at the time will remember. Credit: Mike Flannigan.

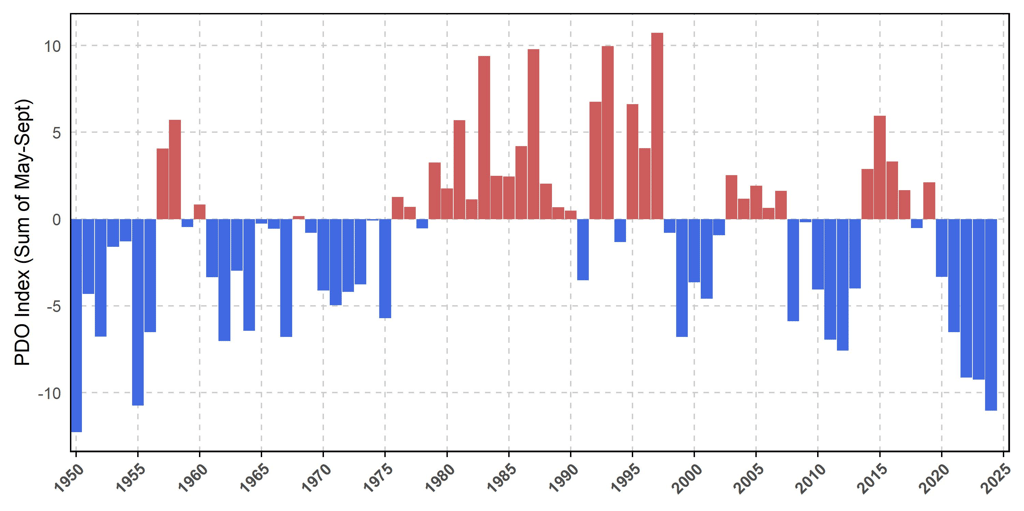

The Pacific Decadal Oscillation has tended to swing between positive and negative phases every 20 to 30 years over the past century or so. Negative phases are at least somewhat correlated with more area burned in British Columbia – with positive phases correlated with less area burned. The interaction of climate patterns with wildfire activity is an ongoing area of study. Credit: NOAA.

Near-term outlook

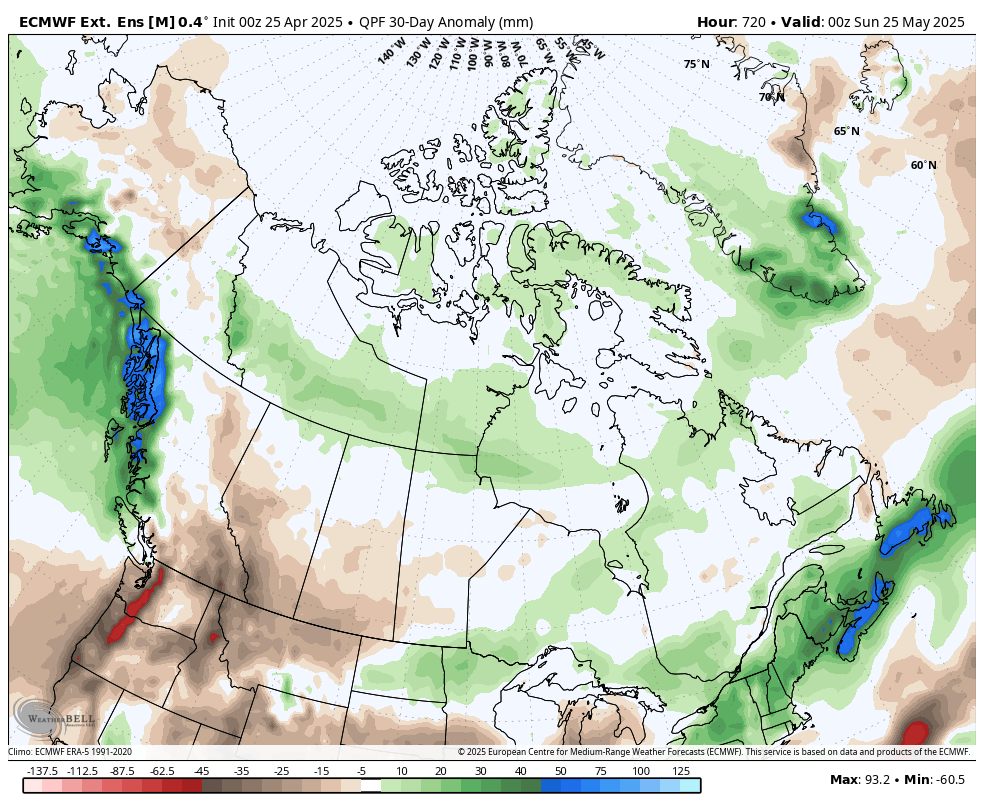

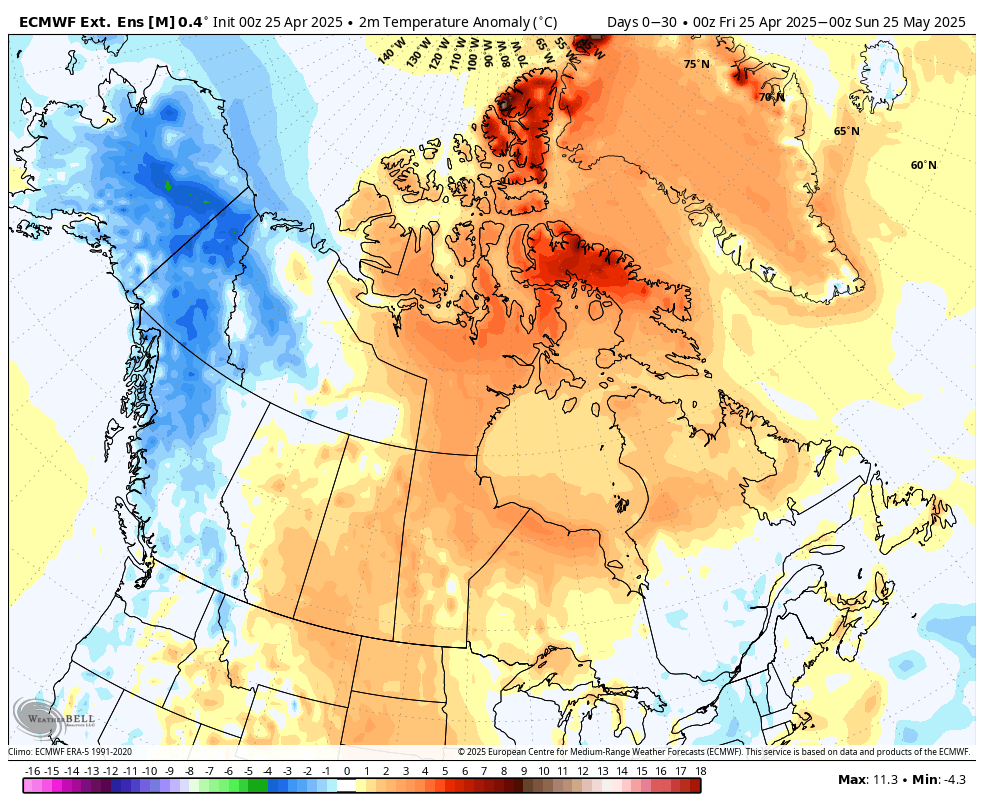

Drier than average conditions favoured across much of British Columbia and Alberta over the next month, according to the ECMWF. Credit: WeatherBell.

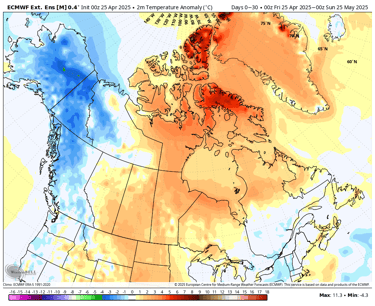

Over the next month or so, long range models are in general agreement that it will be drier than average over much of the British Columbia interior and Alberta, with most storm systems passing to the north. During this same time frame, warmer than average conditions are favoured east of the Rockies. There are mixed signals as to whether British Columbia will be warmer or cooler than average.

Warmer than average conditions are favoured east of the Rockies over the next month, according to the ECMWF. Credit: WeatherBell.

These conditions would support Alberta’s fire season commencing on cue in the coming weeks, so expect activity to ramp up somewhat as we get into the month of May. Most of British Columbia, save for the northeast, should remain quieter for the time being.

Long-term outlook

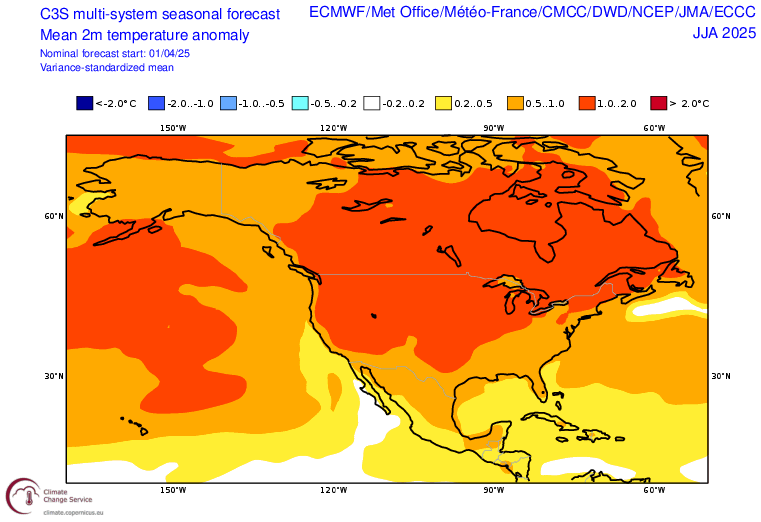

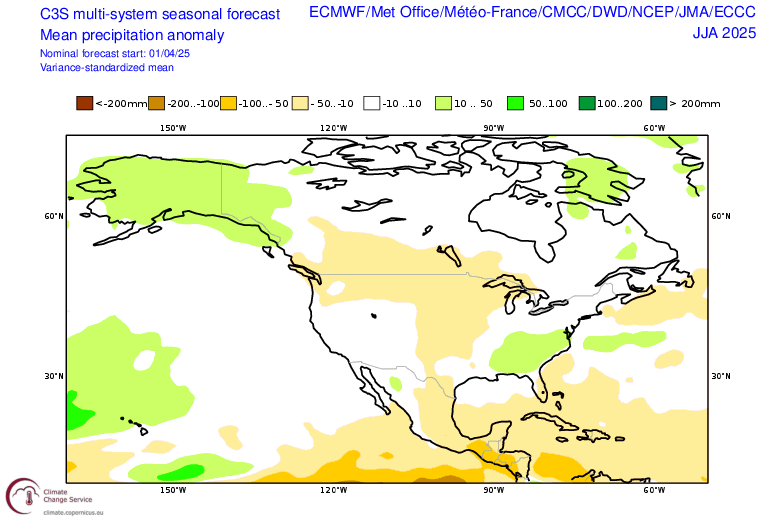

Warmer than average conditions are favoured this summer (June, July, and August) throughout much of Canada and the United States. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service.

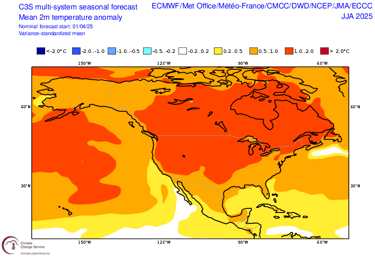

Long-range models possess limited skill (especially in summer), but across the board, they seem to be consistently homing in on a warm, dry signal for much of western Canada. This is consistent with what we spoke of earlier, with respect to signals from climate driver patterns. The speed and severity with which drought develops across the landscape will be heavily dependent on how much our seasonal wet period shows up this year. If it fails to sufficiently materialize – and hot, dry weather persists through summer – we will see the rapid onset of drought across broad areas. At worst, this could come to resemble a year like 2021 in its impacts to wildfire activity, agriculture, and water supply.

Drier than average conditions are favoured this summer (June, July, and August) throughout much of western Canada, and the northern/central United States. Note that long range precipitation forecasts have notoriously low skill. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service.

In sum, it seems more likely than not that this summer will be warmer and drier than average across a large area of western Canada. This means another active wildfire season could be in the cards.

It is important to note that an abundance of fire weather days (hot, dry, and windy) doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll have a lot of wildfire. Many wildfires, and some that grow to be very large, are preventable. Assuming a forest area doesn’t get a rash of dry lightning, being cautious with fire can save us a lot of smoke.

How to stay prepared

They say, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” The list of wildfire disasters in Canada continues to grow, so it behooves all of us to be prepared and proactive – especially for those living in wildland-urban interface areas.

Here are some practical tips for protecting your family, property, and communities this summer:

Be fire smart. Learn about how to limit the potential of fire spread in your community and around your home

Have an emergency plan

Make a 72-hour emergency kit

Be careful with fire when in the outdoors, and observe all fire bans

Alberta and British Columbia both have excellent websites and apps to keep you informed and safe throughout wildfire season.

And now, may my forecast for yet another hot, smoky summer be wrong!