2025 Western Canada Drought Outlook

Kyle Brittain

4/16/202511 min read

Spring is finally in the air, which means pollen, tractor dust, and wildfire smoke may soon be, too.

I’ve already heard lots of questions, like “are we still in a drought?” or “how bad will this year’s wildfire season be?” To find out what could be in store for warm season ‘25, we’ll take a closer look at everything from the dirt beneath our feet to the temperature of the oceans thousands of kilometres away.

But first, let’s talk about how winter went down.

Spring crocuses catching some rays, overlooking the Bow River in southeast Calgary.

Where's all my snow?

This past winter, I went Nordic skiing a grand total of two times – and neither of those times were in Alberta. This came as somewhat of a surprise, given the fairly high confidence that winter 2024-25 would be snowier than average in the mountains of western Canada (for reasons we will discuss shortly). Instead, though improved over spring 2024, British Columbia’s snowpack is only at 79% of normal, while parts of the Alberta Rockies snowpack are at near-record low levels. For one particularly startling anecdote, Banff saw its driest winter on record, recording just 15.8 mm of precipitation between December and February. Poor skiing, indeed!

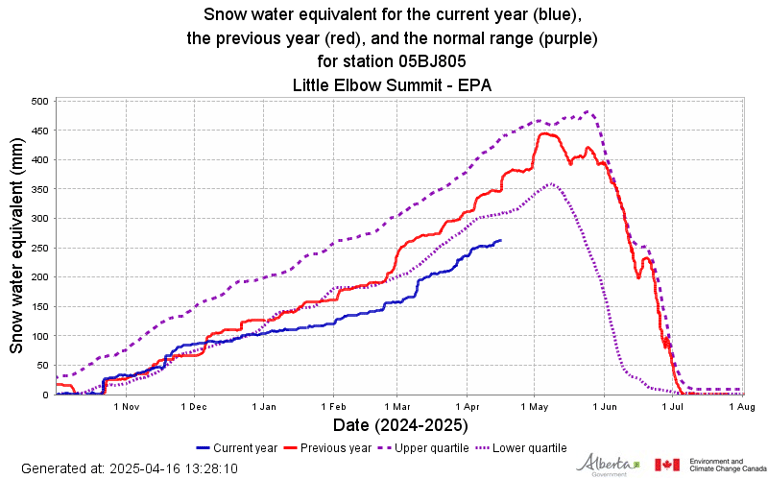

The Rockies southwest of Calgary are seeing well-below normal snowpacks. This site, at Little Elbow Summit, is seeing one of the lowest snowpacks since records began here in 1984. Credit: Government of Alberta.

That being said, the snowpack situation varies regionally across British Columbia and Alberta. A series of early spring storms improved moisture conditions across much of southern British Columbia, the Rockies north of Banff, and the plains of central Alberta, bringing the mountain snowpack to near normal in many ranges.

In Alberta, this has been good news for the headwaters of the North Saskatchewan, Red Deer, and even Bow River basins, which will help to improve spring runoff and stream flows into early summer. Further south, our basins that are heavily tapped for the irrigation of cropland, including parts of the Bow River, Oldman, and Milk River basins, haven’t been as lucky. In these areas, well-below normal spring runoff is expected given low snowpacks and the likelihood of an early melt. Of course, all of this comes with the important caveat that we could still see significant precipitation events in these areas right through the month of June.

In British Columbia, it remains very dry in the Central Coast, Cariboo/Chilcotin, and Peace regions. Should these trends persist, I would be on the lookout for elevated fire danger in these regions much earlier than normal this year. However, the same important caveat exists as for Alberta, in that late spring and early summer can bring significantly wet periods, usually in the form of moist upper level low pressure systems. The question is whether any of these will materialize this year.

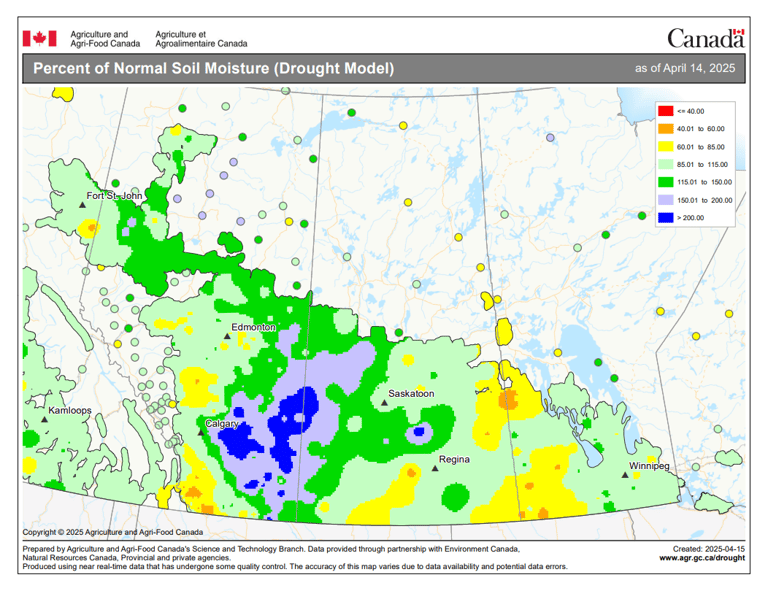

Soil moisture is above normal as of mid-April across much of southern and eastern Alberta, as well as western Saskatchewan. Credit Agriculture and Agri-food Canada.

Compared with the Rockies, adjacent parts of the Prairies saw plentiful winter snow. This continues a relatively wet trend that has been in place across parts of southern and southeastern Alberta as well as western Saskatchewan since last fall, which bodes well for planting season for these areas as we get into May. Further east, parts of southern and southeastern Saskatchewan as well as southwestern Manitoba have seen continued dry conditions, causing local drought to worsen.

Taking stock

Before looking at what could happen this year, let’s get a better sense of the lay of the land (and oceans) by looking at what is happening.

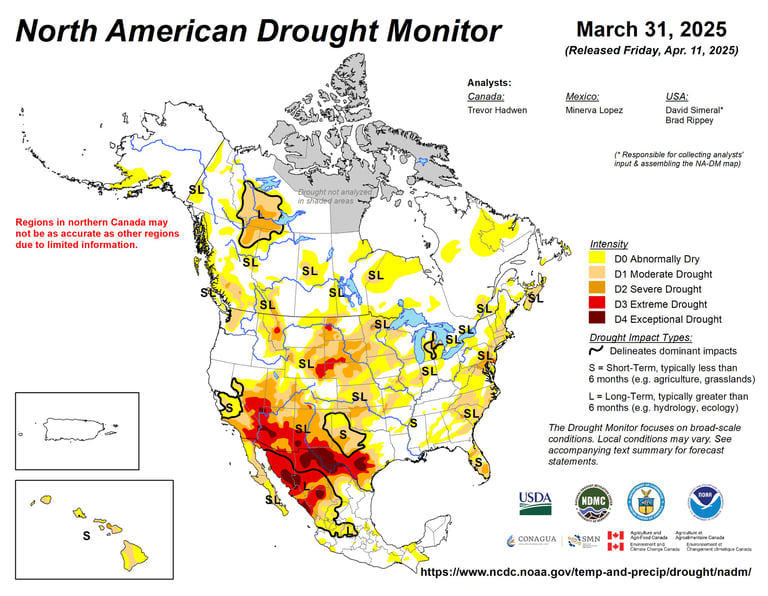

Credit: North American Drought Monitor.

According to the latest drought monitor map, there are pockets of severe drought in parts of British Columbia’s Cariboo/Chilcotin region, as well as in southwestern Alberta, where mountain snowpacks are well below average. There’s also the persistent blob of severe drought in northeast British Columbia, northwest Alberta, and southern Northwest Territories – a relic of the winter of 2022-23, which has been supporting large, multi-year fires. South of the 49th parallel, severe to extreme drought is more widespread in certain regions, especially in parts of the Northern Plains and from Texas to the Desert Southwest.

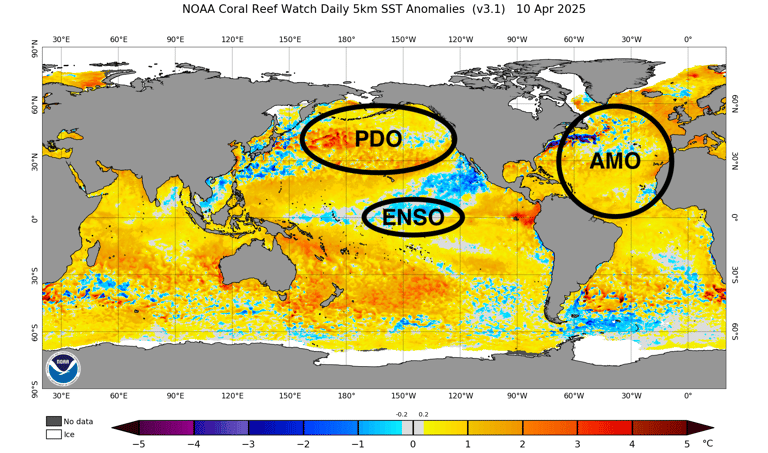

Sea surface temperature anomaly patterns that are important for western Canada include ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation), the PDO (Pacific Decadal Oscillation), and to a lesser extent, and the AMO (Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation). As of mid-April, ENSO is neutral, the PDO is in its negative phase, and the AMO is in its positive phase. Credit: NOAA. Annotations mine.

Another way to make sense of our changing weather and climate patterns is to look at the temperature of the oceans around North America, and how much warmer or colder they are than average in specific areas. These can be important for how they influence the shape of the jet stream in the atmosphere above, and its associated areas of rising and sinking air, resulting in the weather we experience. Hang with me for a little bit here.

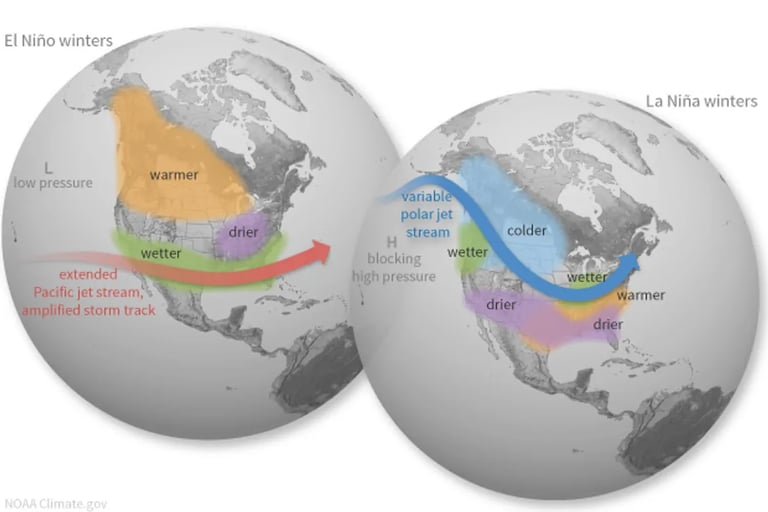

Many of these sea surface temperature anomaly patterns oscillate between different phases over time, causing different effects on weather and climate. For instance, you may have heard of “El Niño” or “La Niña”, which are the warm and cold phases of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) pattern, respectively – a sea surface temperature pattern that changes on the scale of months to years in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.

A strong El Niño, for instance, tends to cause much different effects in the atmosphere than does a strong La Nina. These effects are felt both near and far, thanks to their influence on the jet stream. In western Canada, ENSO tends to be our most important “climate driver” pattern, providing a measure of skill in long range forecasts when the signal is strong. For example, La Niña winters tend to be colder and snowier than average in the mountains of western Canada, while El Niño winters tend to be warmer and drier than average across much of western Canada.

The different influences of El Niño and La Niña on North American winters. Credit: NOAA.

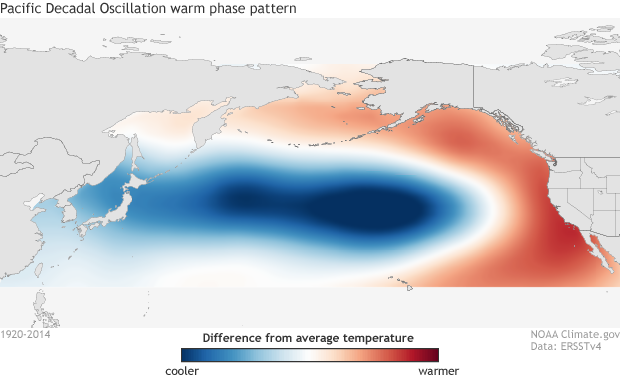

The warm (positive) phase of the PDO. Credit: NOAA.

Right now, we are in the cold phase of the PDO (opposite of what is shown in the graphic above), given that temperatures in the central North Pacific are warmer than average compared with areas along the coast of North America. We have also just transitioned from a brief, weak La Niña in the tropical Pacific this winter into neutral conditions (neither El Niño nor La Niña). And this is why I had mentioned above that based on these climate patterns together, we would tend to have a higher confidence in a colder and snowier winter than average across western Canada. But this didn’t happen.

Long range forecasting is hard

Now that we have gotten all of that out of the way, we can look ahead to what may be in store. It should come as no surprise that the climate system is complex, making it hard to predict the future several months down the road. Moreover, climate drivers like ENSO tend to have their strongest influence on the atmosphere during the Northern Hemisphere winter, making summer a bit of a wild card – but that’s not going to stop me from taking a crack at it!

Model forecasts only possess so much skill (with almost no skill for long range precipitation), but agreement between models of varying agencies suggests they may be picking up on something important. In making my summer forecast, I am relying heavily on my assessment of the “lay of the land (and oceans)” I spoke of earlier. This can help me select other years as analogs that looked similar to this year, and noticing how those years evolved over time. If the similarities between them are consistent and significant, this can increase confidence in my forecast.

And so, I hand-picked the top 5 years that looked most similar to spring 2025 in terms of ENSO phase and transition, PDO phase, spatial patterns of sea surface temperature anomaly and drought, and so on. Ranked from more to less similar, they are:

1967, 2009, 2018, 2001, and 2021…with 2006, 2012, and 2017 as the runners-up.

All of these years began in (mostly weak) La Niña or ENSO neutral conditions, were ENSO neutral through summer, and were mostly paired with negative PDO – much like this year.

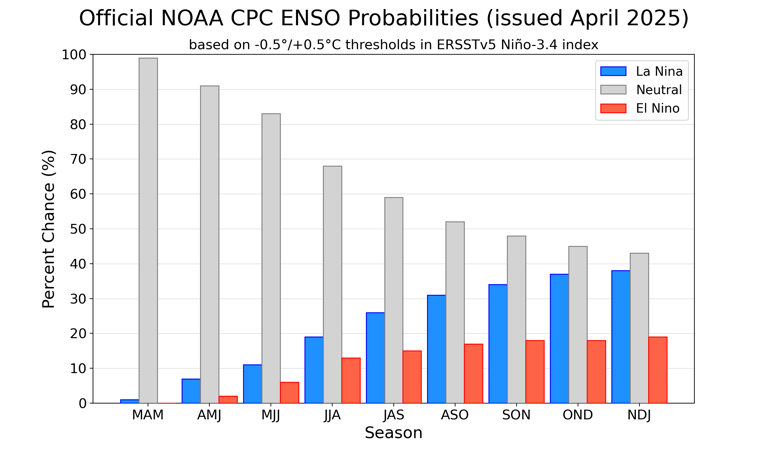

ENSO neutral conditions favoured to persist into fall. Credit: NOAA/CPC.

I’ll quickly (and very broadly) introduce you to one more sea surface temperature anomaly pattern in the Pacific that we need to look at – but this one is farther north of the tropics, and closer to home. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is sort of like a longer-term ENSO pattern, on the scale of decades, with differences in sea surface temperature anomaly between coastal areas of North America, and the central North Pacific further west. The warm (positive) phase has warmer than average sea surface temperatures along the coast of North America and is “El Niño-like”, while the cold (negative) phase has colder than average sea surface temperatures along the coast of North America, and is “La Niña-like”.

NOAA’s official ENSO forecast has neutral conditions persisting at the highest probability through summer, while long range model ensembles show negative PDO conditions persisting in the North Pacific, with relatively cooler sea surface temperatures along the west coast of North America compared with areas farther west.

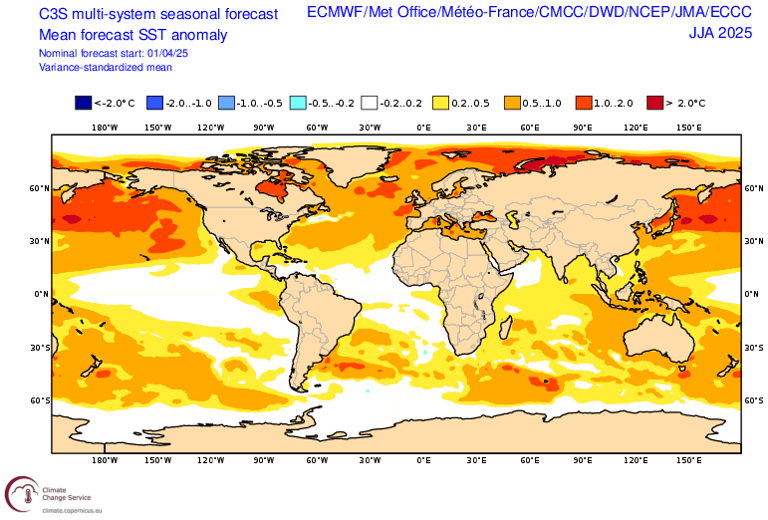

The ensemble mean of several long range models favour an ongoing cold PDO, as seen by the relatively lower sea surface temperature anomalies along the west coast of North America. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service.

My take? Worsening drought likely across western Canada this summer

ENSO neutral or La Niña conditions, paired with a negative PDO, often lead to drier than normal summers across much of western Canada. This particular pattern can make for a weaker, more wavy summertime jet stream across western Canada that’s more prone to getting stuck in "blocking" patterns. Beneath and downstream of strong, upper high pressure ridges, air sinks and dries while temperatures increase – which, if occurring over many days, can lead to drought. And this is indeed what tended to play out in those analog years, with a few exceptions.

Past years like this have typically seen worsening drought and elevated wildfire risk across western Canada – especially in the British Columbia interior. Think of all the hot, dry, smoky summers coming out of La Niña winters in recent years, paired with a negative PDO: 2023, 2021, 2018, and to a certain extent, 2017. Looking back, 1967 also had bad wildfires in southeastern British Columbia, which is my top analog for 2025.

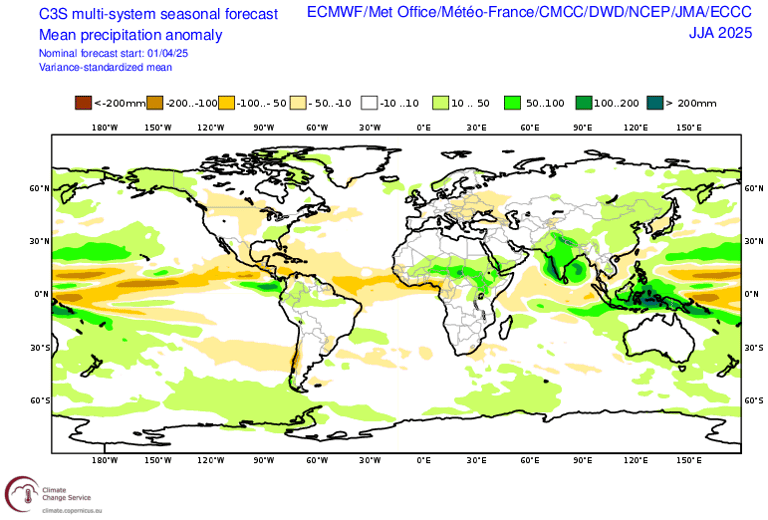

The ensemble mean of several long range models favours drier than normal conditions across much of western Canada, as well as the central and northern United States this summer. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service.

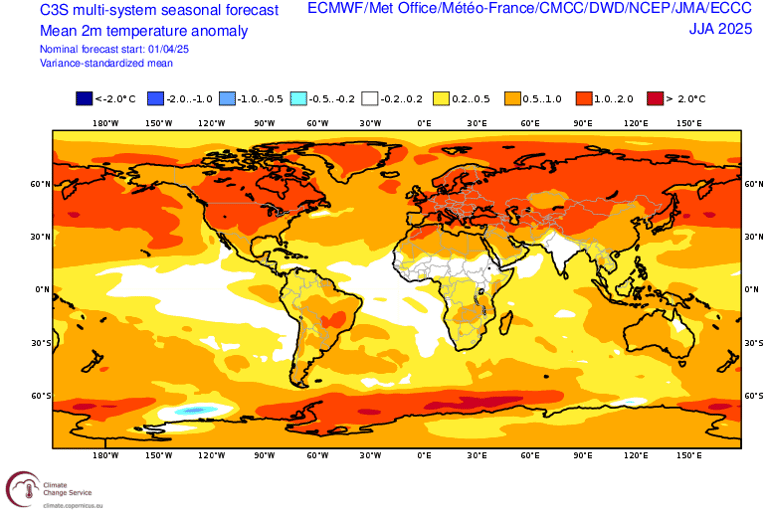

The ensemble mean of several long range models favours warmer than normal conditions across much of Canada and the United States this summer. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Long range model ensembles are also generally predicting a warmer and drier summer than normal across much of western Canada and the Northern and Central Plains of the United States. How might this play out in terms of impacts? Well, for one, it could be another hot and smoky summer for many across the country – especially during the back half summer, as fires get going in the mountain forests of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. Even now, though, the snow has already melted out earlier than normal across much of the forest areas of northern Saskatchewan, Alberta, southern Northwest Territories, and northeast British Columbia. This means it’s already wildfire season there, with forested lands only awaiting the arrival of hot, dry, and windy weather and ignitions, especially ahead of green-up.

Current model forecast trends also suggest drought may expand and worsen across much of western Canada and the central and northern United States. This could come to resemble a year like 2021, with impacts on agricultural yields and water supply. While surface soil moisture is currently in good shape across much of Alberta and Saskatchewan, rapid drought development could occur with prolonged periods of hot, dry weather. In Canada’s Prairie breadbasket region, nearly 50% of all precipitation in a given year falls in summer – mostly in the form of thunderstorms. Being far away from any large, warm bodies of water, this local cycle of convective precipitation relies heavily on local sources of moisture, which typically comes from evaporation of soils and transpiration of crops. Thus, as your local farmer might say, “it’s important to get the pump primed” early in the season, to have a shot at kicking off this water cycling process. Sinking air, dry soils, and wildfire smoke together would work against it, by stifling thunderstorm development.

Mounts Cornwall and Glasgow, southwest of Calgary, looking plastered in snow. However, looks can be deceiving, as the snowpack is well-below average as of mid-April.

Lastly, there’s concern for low mountain runoff in parts of British Columbia and Alberta, given below normal snowpacks in certain areas and a warm, dry forecast. Snowmelt provides an important source of slow-release water that serves as water insurance into summer, filling streams that provide water supply for things like hydroelectric power generation and irrigation, as well as industrial and municipal use. A hot and dry summer could lead to lowered reservoir levels and decreased streamflow in summer, especially for those basins that lack the benefit of late summer glacial melt. This could lead to water scarcity and the potential for water restrictions down the road.

It’s not entirely hopeless, though. Sometimes things don’t pan out as expected – much like this past winter. I had 2009 and 2012 as analogs for this season, which had wetter than normal conditions in much of British Columbia during those summers, as well as in much of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 2012. A couple of large, moisture-laden systems at the right time could make all the difference. This year, it may help that soils are quite moist to start the season in much of the western Prairies.

If persistent upper troughing happens to set up along the British Columbia coast, it would likely be wetter than normal for much of British Columbia and Alberta. However, more often than not, we tend to see west-focused upper ridging in summers like these, leading to hot and dry weather across most of western Canada. There may also be notable, regional variation in precipitation patterns – similar to 2023, when a couple of significant upper level lows brought above normal rainfall locally to west-central Alberta. Farmers in this area may have been tempted to think “what’s everyone complaining about?” when most of the rest of the west was very dry. Moreover, localized areas could still see extreme precipitation events associated with thunderstorm activity. It’s just a matter of wait and see at this point.

So while anything could happen, it seems the dice are loaded in favour of a warm, dry summer in western Canada, which could lead to yet another year of worsening drought and associated impacts.