Fall and Winter Forecast 2025/26

Will the Polar Vortex make headlines again this winter? Let's take a deep dive into the particulars of the fall and winter forecast for western Canada.

Kyle Brittain

9/21/2025

Fall is apparently here in western Canada, but it sure hasn’t felt like it yet.

How long will the warmth continue? Are there any signs of what winter could be like? Could the term “Polar Vortex” make a comeback? Read on to find out more, as we look to predict the future together.

Taking Stock – the Current Climate Setup

Seasonal forecasts always begin with the big picture. To understand where the season could be headed, we first look at oscillating global patterns of ocean temperatures and upper-atmospheric winds.

These large-scale drivers, like stones dropped into a pond, send out “ripples” that can influence weather thousands of kilometres away. While each driver has its own rhythm, their combined effects can create very different seasonal outcomes. And without a doubt, it can get complicated.

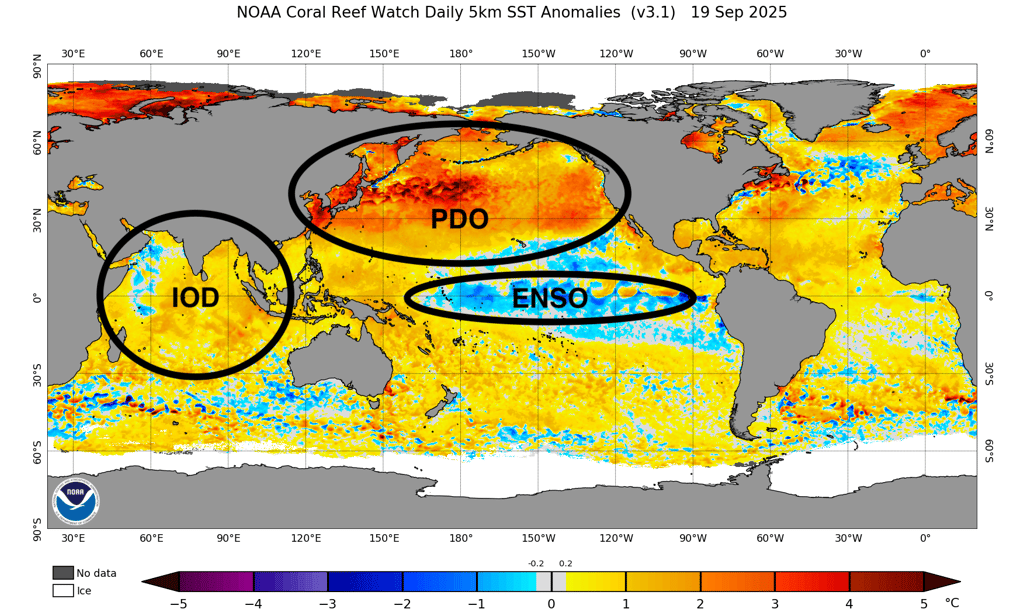

A cursory look at the current map of global sea surface temperature anomalies (difference from normal) reveal a couple of important features: signs of an emerging La Niña in the tropical Pacific, and significant warmth across the entire North Pacific. Annotations mine. Credit: NOAA.

ENSO – La Niña likely on the horizon

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) tends to be the most important climate driver on a global scale. It alternates between:

El Niño (warm phase) – warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific

La Niña (cool phase) – colder-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific

Neutral, when neither dominates

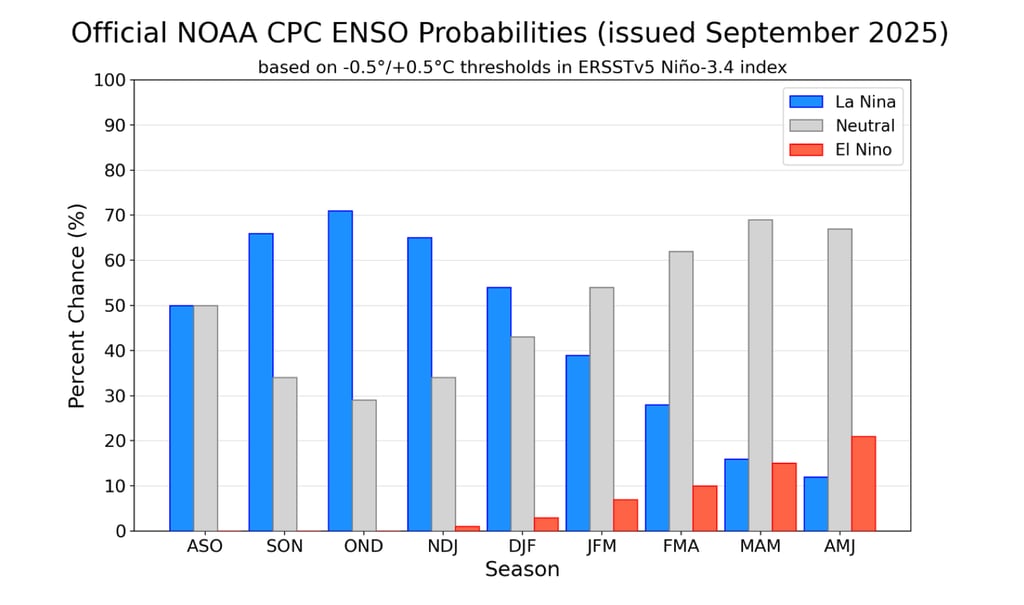

While we’re currently seeing ENSO neutral conditions, the U.S. Climate Prediction Center is predicting that a weak La Niña could develop in the tropical Pacific between October and December. This is being driven by stronger-than-normal easterly trade winds, bringing cooler, deeper water to the surface.

While the chances of La Niña decrease somewhat in the period from December to February, it’s still the favoured mode through the rest of winter.

NOAA CPC has a 71% chance of a La Niña developing during October to December. It decreases to a 54% chance from December through February. Credit: NOAA.

PDO – an Unusual Negative Pattern

Beyond the tropics, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is the most important mode of sea surface temperature variability across the North Pacific.

Currently, the PDO is negative, driven by extreme warmth near Japan and eastward along the Kuroshio Extension. However, unlike a typical negative PDO—which usually features cooler than normal sea surface temperatures along the west coast of North America—the northeastern Pacific is also unusually warm. Thus, presenting as a more El Niño-like pattern along the west coast of North America, it is undoubtedly contributing to the abnormally warm weather we’ve seen across western Canada so far this fall.

IOD and QBO – Additional Players

Two other key oscillations are at work:

Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD): Negative Phase

Warmer-than-normal waters dominate the eastern Indian Ocean, while cooler anomalies sit to the west

This tends to boost tropical thunderstorm activity near Indonesia and the western Pacific

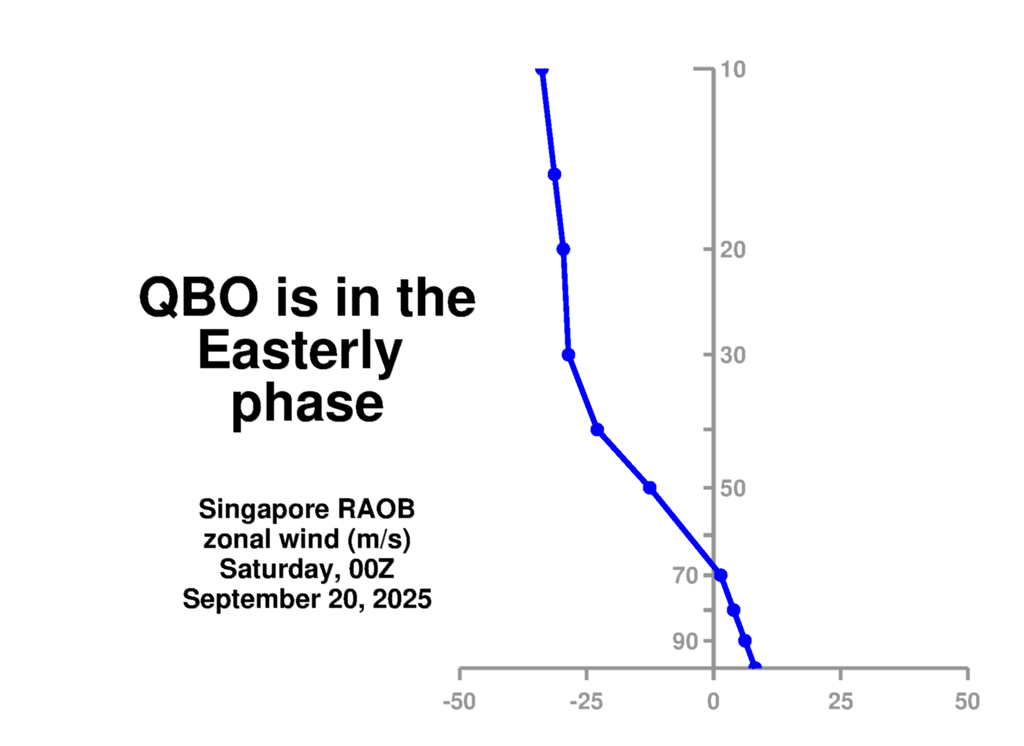

Quasi-Biennial Oscillation (QBO): Easterly Phase

The QBO tracks alternating layers of easterly and westerly winds in the tropical stratosphere

It flips phase roughly every 27 months, hence the term “quasi-biennial”

An easterly QBO tends to be linked to a weaker Polar Vortex

A weather balloon launched from Singapore at 00Z on Saturday, September 20 reveals descending easterly winds in the stratosphere. The easterly phase should peak during the winter season. Credit: NASA.

How These Drivers Interact

When these oscillations align, their combined effects can reinforce one another. This can enhance their overall effects, bringing a higher confidence of a given forecast outcome.

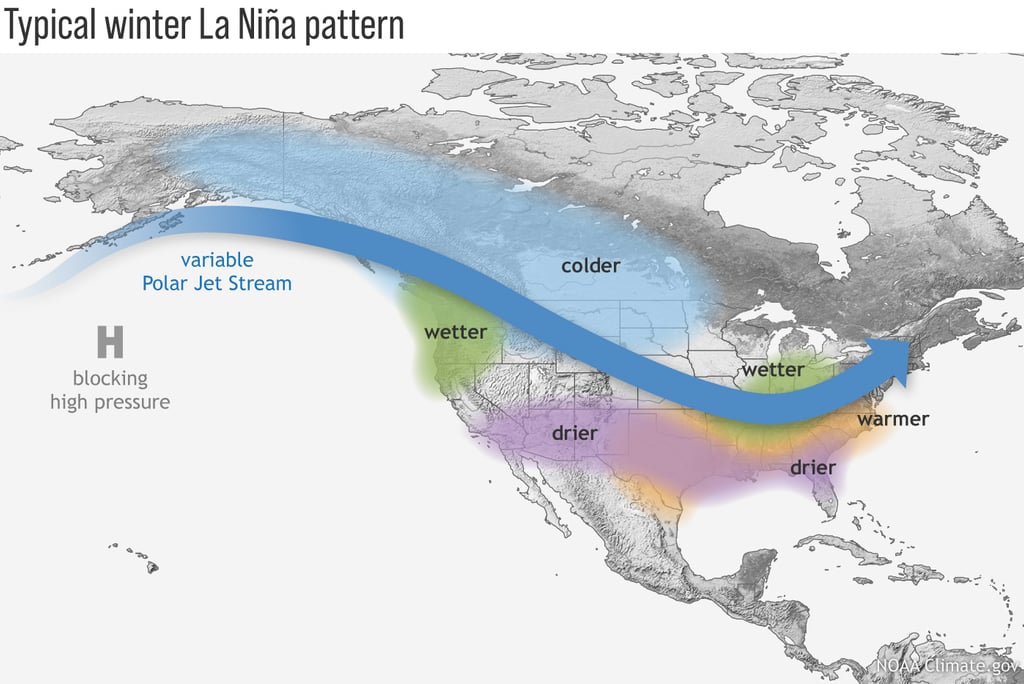

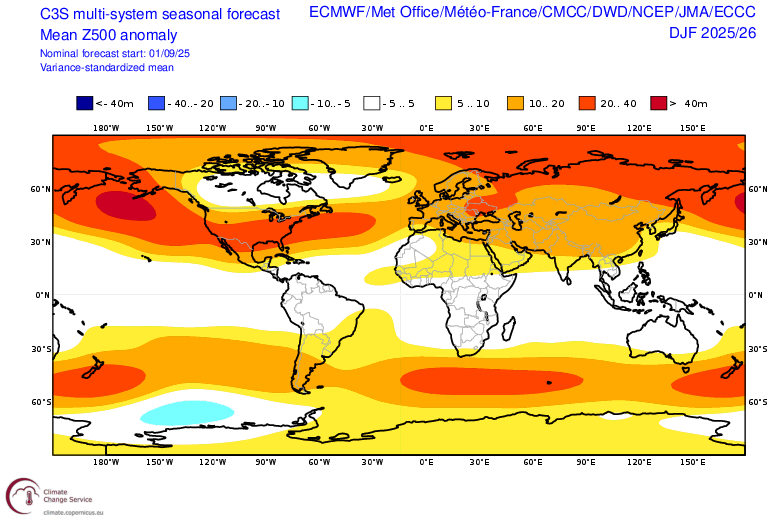

This winter, the combination of an easterly QBO, negative PDO, and negative IOD represents a more La Niña-like pattern overall, in sync with the weak La Niña forecast to emerge in the tropical Pacific. This likely explains why long-range models are generally forecasting typical La Niña -like conditions through the Northern Hemisphere winter, with cooler than normal temperatures and above normal precipitation forecast for much of western Canada.

Typical winter weather patterns across North America during a La Niña. Credit: NOAA.

Their alignment also sets the stage for two other key influences:

A stronger Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO)

A weaker, more unstable Polar Vortex

The MJO – A Cyclical Tropical Thunderstorm Pattern

The Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) represents a pulse of thunderstorm activity that travels eastward across the tropics, from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific, on 30–60 day cycles.

When the MJO is strong:

It injects huge amounts of moisture and heat into the atmosphere

This energy can reshape the jet stream, influencing storm tracks far downstream

Forecasts can improve to two or more weeks

This winter, the negative IOD and La Niña warm pool surrounding the Maritime Continent (the archipelago consisting of Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea) will likely enhance MJO activity, which can be further enhanced while the QBO is easterly. As the MJO moves into later phases, it often causes an extended Pacific jet and drives moisture-laden atmospheric rivers toward the west coast of North America, bringing heavy rain and high freezing levels.

The Polar Vortex – Weak and Wobbly This Year?

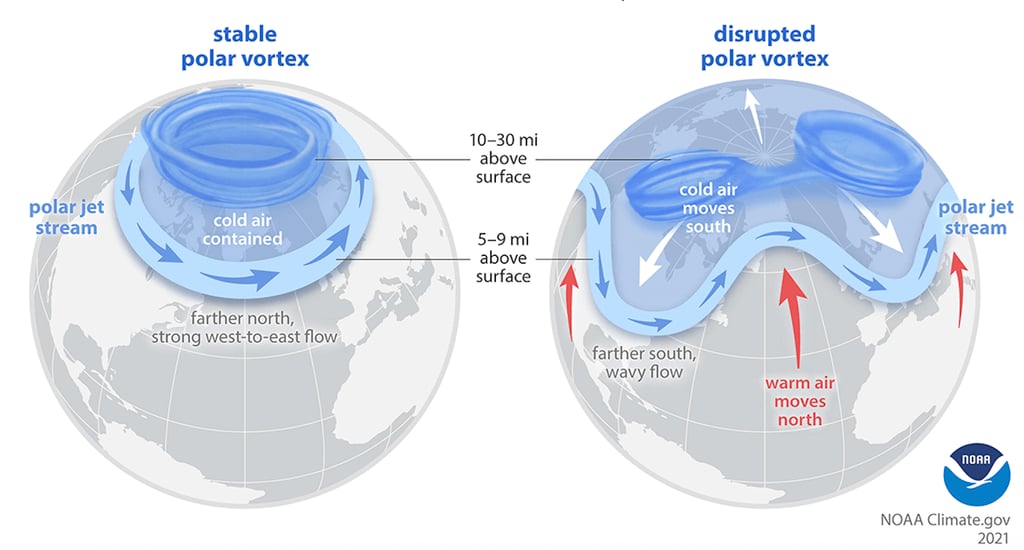

The Polar Vortex is a band of strong westerly winds encircling the Arctic stratosphere.

When healthy and strong, it keeps cold air bottled up near the pole. When weak, it can split, shift, or collapse entirely, unleashing Arctic outbreaks into mid-latitudes.

This winter’s background state—a weak La Niña and easterly QBO—favours a weaker Polar Vortex.

A wavy, sluggish polar jet stream is more prone to blocking events, where high-pressure systems stall and lock weather patterns in place

Strong MJO pulses can further disrupt the vortex, causing it to collapse in an event known as a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW)

SSWs can influence the weather for many weeks afterwards – with the risk of cold air outbreaks deep into the mid-latitudes

A stable polar vortex at left, versus a disrupted polar vortex at right. Both strong and weak polar vortices can influence upper tropospheric winds, which can influence the weather at the Earth's surface. Credit: NOAA.

The Seasonal Forecast: Fall into Winter

October: El Niño-like Pattern Holds

For the next few weeks, a rather El Niño-like pattern will prevail:

A strong, eastward-shifted Aleutian Low will drive a powerful jet into British Columbia

Lots of rain for the coastal mountains of central and northern BC – with storms potentially being infused by more moisture than normal, given warmer than normal sea surface temperatures in the northeastern Pacific

Temperatures in these regions will run near normal, while much of the rest of western Canada will remain warmer than normal

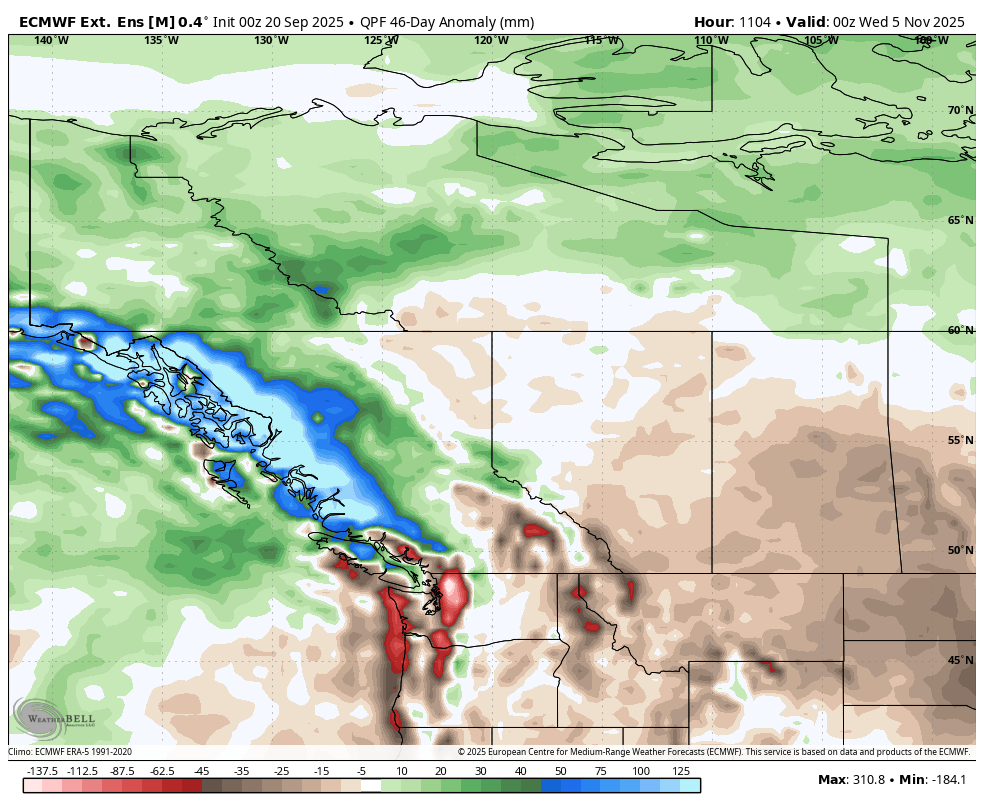

46-day precipitation anomaly from the Euro Weeklies. An active storm track through central and northern British Columbia will bring much wetter than normal conditions to the Coast Mountains in those regions. Credit: WeatherBell.

November–December: Transition to La Niña-like Conditions

As fall progresses, the Pacific jet should retract westward, allowing:

Persistent high pressure to form off the west coast

Troughing downstream over the continent

Colder air to spill southward into western Canada

By late November and December, we should begin to see the first true wintry conditions affecting BC and Alberta.

Long range model ensembles reveal persistent, strong upper ridging off the west coast of North America, with downstream troughing over the continent. Strong, Alaskan blocking can also be favourable for stretched polar vortex events as opposed to SSWs, which may be more favourable with Greenland blocking. Credit: Copernicus Climate Change Service.

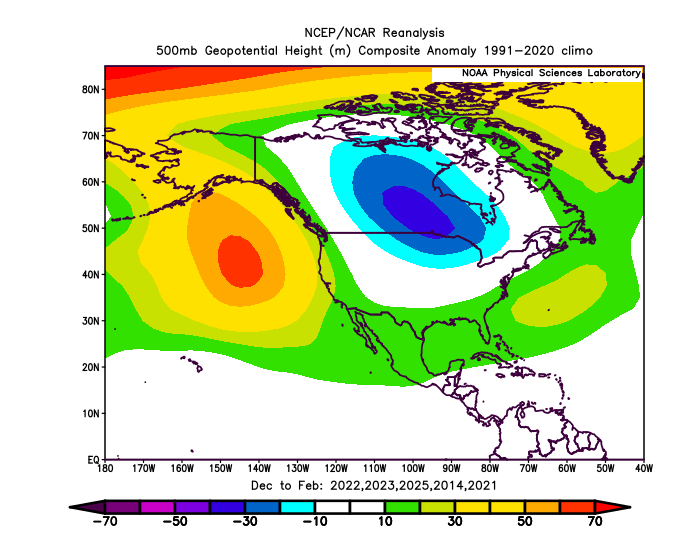

Analogs Support the Pattern

Past winters with similar sea surface temperature patterns offer clues for how the winter may play out. In the current climate regime, several of the past few winters have looked quite similar. Perhaps the strongest analog for this season is the winter of 2021-22, with weaker but notable analogs including 2022/23, 2024/25, 2013/14, and 2020/21.

Composite analysis of these years shows:

Frequent blocking highs off the west coast of North America, with downstream troughing over the heart of the continent

Colder than normal temperatures across western Canada

Snowier-than-normal Rockies and interior BC

Potentially drier-than-normal conditions along the South Coast and Vancouver Island

Ridging off the west coast, with troughing over the continent, have been common features during similar winters in the recent past. Credit: NOAA.

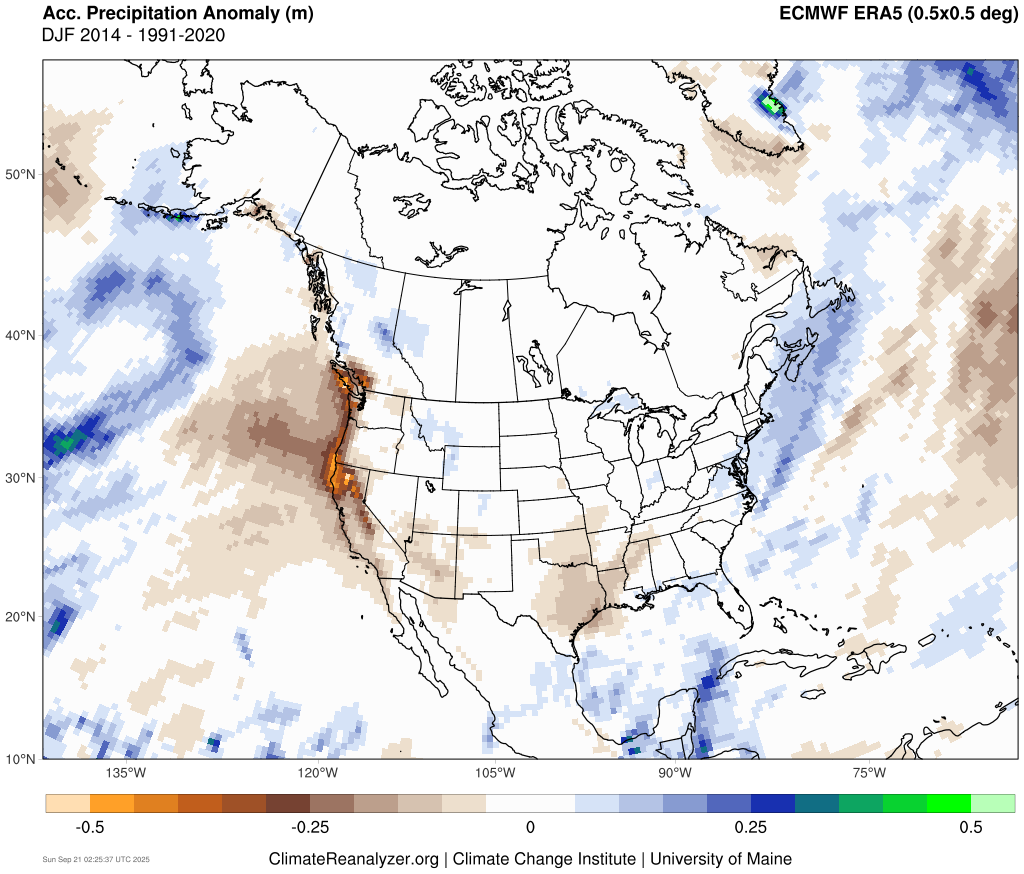

A key wild card – especially for the BC coast – is how strong and persistent the ridging off the coast becomes. When significant, it can block Pacific moisture and cause sinking air on the large scale that brings about well-below normal winter precipitation. This was certainly true of the winter of 2013/14, which was the first winter of “The Blob”. That year, persistent upper ridging was associated with a marine heat wave owing to a “blob” of above normal sea surface temperatures off the west coast. This resulted in a very dry winter down much of the west coast of North America.

ERA5 Reanalysis showing anomalously dry conditions east/southeast of the mean upper ridge occurred down the west coast from Vancouver Island and the South Coast region to California, in the winter of 2013/14. Credit: Climate Reanalyzer.

Other Factors to Watch

Arctic Sea Ice: Coverage is currently below normal as of September 21, but not extreme.

Warmer than normal, open water near the northern Eurasian coastline and in the Beaufort Sea could boost October snowfall over adjacent lands

This can cause areas of anomalously high surface pressure that can contribute to a wavier polar jet stream, with enhanced blocking downstream

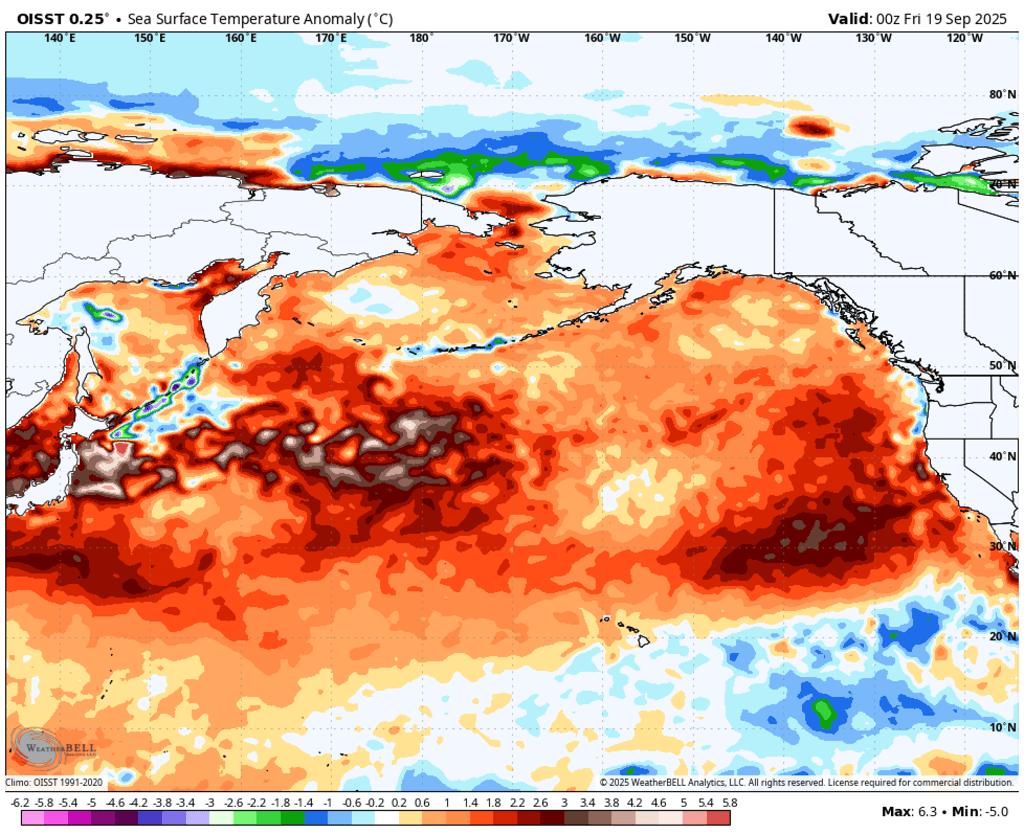

North Pacific Marine Heat Wave:

A significant, basin-wide marine heat wave is ongoing, with pockets of anomalies approaching 3°C or more

Significant, negative ecological impacts likely

Patterns of warmth will continue to influence storm tracks and the jet stream throughout the winter, with unexpected climate impacts possible

All-time record warmth is ongoing across the North Pacific, with the most extreme marine heatwaves near and east of Japan, as well as off California. Some areas are seeing isolated pockets of anomalies in excess of 3 or 4°C. Credit: WeatherBell.

The stormy pattern in the Gulf of Alaska could cool sea surface temperatures near parts of the Aleutian Islands in the coming weeks, and a La Nina-like winter could cool sea surface temperatures along the west coast of North America, helping it to resemble a more normal negative PDO pattern once again.

There are lots of moving parts to consider in our interconnected climate system. But the way things appear to be coming together raises confidence in a more classic, La Nina-like winter. And yes, the term “polar vortex” could certainly make headlines again this winter.

Winter Forecast Summary:

Temperatures will likely tip colder than normal overall across British Columbia and Alberta, with a few shots of truly cold Arctic air at times – especially east of the Rockies.

Above normal snowfall is possible through the Rockies and interior ranges of British Columbia, as well as some adjacent areas of the Prairies

Winter could trend wetter or drier than normal along the South Coast, depending on the location and intensity of ridging off the coast, and the Pacific storm track

A few warm, wet atmospheric river events could bring heavy rain along the coast, elevated freezing levels, and heavy wet snow across the higher elevations of the mountains of western Canada. These could also result in strong Chinooks across southern Alberta

In all, I am slightly more optimistic for a snowier than normal winter in the Rockies this year, compared to last. Here’s to better skiing this winter season!

To see how my summer forecasts for drought, wildfire, and Prairie tornadoes performed, click this link.