Why Chinooks Can Trigger Headaches

Kyle Brittain

2/3/20264 min read

When the weather gets in your head

Do changes in the weather make your head hurt? If so, you’re not alone. Studies show that many people who experience headaches—including up to 50% of migraine sufferers—report weather changes as a trigger.

This is especially true east of the Alberta Rockies, where rapid weather shifts are common. In winter, Pacific air often flows across the mountains and warms as it descends on the lee side, producing a wind known as a Chinook. These winds can cause sudden temperature spikes that melt snow in a matter of hours.

For some, this abrupt warmth is a welcome break from winter’s grip. For others, a Chinook can be a harbinger of pain.

Many people report headaches at various stages of a Chinook event. But is there a scientific explanation behind this phenomenon?

What the research says

A study from southern Alberta

In southern Alberta, a study published in 2000 found an increased probability of migraines in two subsets of sufferers: those who experienced headaches both before and after the onset of Chinook winds.

However, the study was relatively small, and its conclusions were challenged by research in other regions of the world where warm, downslope winds occur. For example, similar increases in headaches could not be consistently demonstrated with the foehn winds of the European Alps.

Weather and headaches:

A complicated relationship

Numerous studies worldwide have attempted to identify which weather changes are most likely to trigger headaches. These studies, however, are notoriously difficult to conduct.

Some researchers compare emergency room visits for headaches with trends in weather variables, while others rely on self-reported headache diaries. Study locations span a wide range of climates and geographies, with varying sample sizes, demographics, and time periods.

Adding to the challenge, headache sufferers often have multiple non-weather-related triggers. The combination of environmental and human factors—along with potential reporting and selection biases—can weaken individual study results.

Unsurprisingly, not all studies agree. But when viewed collectively, some consistent patterns begin to emerge.

The key weather variables linked to headaches

According to a 2025 review that examined 31 studies, three meteorological variables appear to play the most significant role:

Temperature

Atmospheric pressure

Air pollution

As it turns out, all three are defining features of a Chinook event.

Anatomy of a Chinook: A three-phase breakdown

To see how these variables interact, let’s walk through a hypothetical January Chinook in Calgary, broken into three phases.

Phase 1: Before the Chinook arrives

A cold air mass is initially in place east of the Rockies, with clear skies and temperatures in the minus teens Celsius. Meanwhile, mild and moist Pacific air begins flowing over the mountain ranges of British Columbia and Alberta.

Over southern Alberta, clouds thicken into a steely grey overcast. Along the western horizon, a classic Chinook Arch sharpens. Near the surface, a brownish layer of pollution becomes increasingly noticeable.

Despite these changes aloft, the surface temperature remains cold with light winds. A few hundred metres above the city, however, warmer and lighter Chinook air flows overhead, creating a temperature inversion. This inversion—combined with weak surface winds—traps air pollution near the ground, causing air quality to deteriorate until the Chinook reaches the surface.

At the same time, as Pacific flow becomes more perpendicular to the Rockies, air pressure begins to fall across southern Alberta.

Phase 2: The Chinook

Eventually, the warm Chinook air erodes the colder, denser surface air. Temperatures rise rapidly by several degrees, and strengthening westerly winds scour out the trapped air pollution.

By this point, air pressure has typically reached its lowest point and remains relatively steady while the Chinook persists.

Phase 3: The Chinook ends

A Pacific storm system moves into western Canada, triggering the development of a low-pressure system over Alberta. As it slides eastward, it pulls cold Arctic air southward in its wake.

In Calgary, the Chinook often ends suddenly with the passage of a cold front. Winds shift abruptly to the north, temperatures plunge, and air pressure rises rapidly. Air pollution may increase slightly again as the Arctic air mass deepens over the city, though usually not to pre-Chinook levels.

Putting the pieces together

If changes in temperature, air pressure, and air pollution contribute to headaches, it’s easy to see why Chinooks are frequent suspects. Before a Chinook, pollution often builds. The beginning and end of Chinooks are marked by rapid swings in both temperature and pressure.

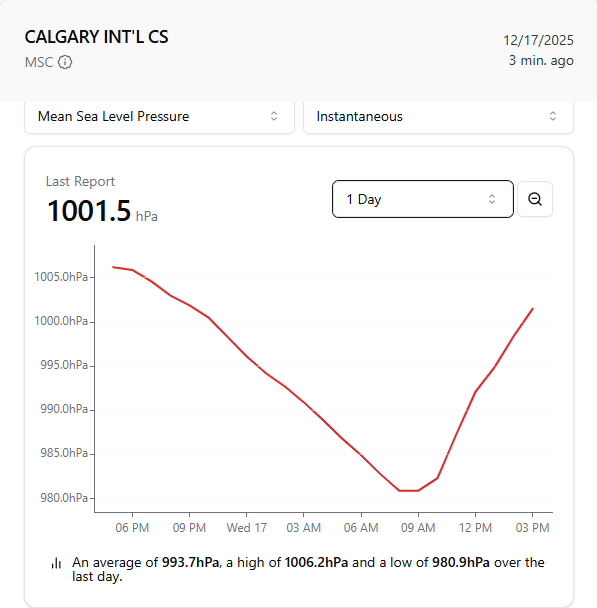

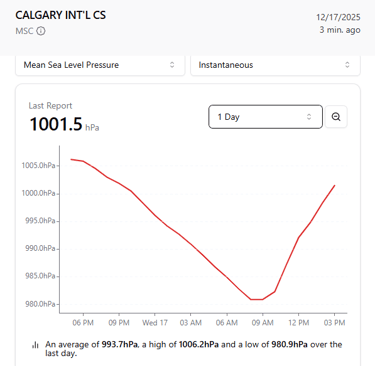

For example, on 17 December 2025, Calgary’s air pressure dropped by more than 25 millibars in just 15 hours—only to rise sharply again later the same day. That’s a meteorological rollercoaster.

Screenshot credit: Northern Mesonet Project.

Even more dramatic was Calgary’s largest recorded daily temperature swing. On 30 January 1989, temperatures plunged from a mild 11.8°C to a bitter –27°C in just over 12 hours—a staggering 38.8°C drop.

Why Chinooks can trigger headaches

The physical mechanisms linking weather changes to headaches are still being investigated. In the case of atmospheric pressure, it is generally accepted that pressure changes affect blood flow within blood vessels, potentially triggering headaches.

On its own, however, pressure change doesn’t appear to tell the whole story. For instance, a drive from Calgary to Banff causes a larger pressure drop than most Chinooks in just an hour and a half—yet people don’t overwhelmingly report migraines during the trip.

It’s more likely that multiple factors act together, increasing the probability of headaches alongside other environmental and human triggers—possibly in ways we don’t yet fully understand.

For now, if you’re sensitive to weather-related headaches, experts suggest minimizing other triggers and keeping your medication close at hand the next time a Chinook is in the forecast.